Use the polar bear craft PDF to print to your computer. Cut out the parts to use in later steps. If your kiddos are old enough you can have them cut the pieces out. However, some of the parts are small.

Turn an ordinary paper plate into a magical polar bear craft this winter. This craft goes perfectly with your preschool unit on arctic animals. The supplies needed are inexpensive. In fact, you probably already have everything you need right in your home or classroom.

Continue through the steps by sending it to your printer, printing on cardstock (recommended), then placing it on your Cricut mat. Be sure to use a light grip mat and don’t press the paper down.

Start by gluing the cotton balls onto the paper plate. This in this step kids can practice dotting the glue all over the plate. Squeezing the glue bottle will help strengthen their finger muscles.

Polar Bear Craft Using a Cricut Machine

There are two ways you can make this craft. First, you can use the template provided to print and cut out the face of the polar. If you are making multiple polar bears and you have a Cricut or Silhouette machine you can print then cut all of the templates right from your machine.

Put a dab of glue on the back of the eyes, nose, and freckles before layering them on the cotton balls. I like to use a little chant for teaching kids how to use glue. It goes, ” dot, dot, not a lot”.

This post may contain affiliate links. That means if you click and buy, I may receive a small commission at no extra cost to you. Please see my disclosure policies for full details.

Next, glue the inner parts of the ears and eyes onto the white circles.

Fletcher did research in old documents and histories to discover what Arthur might have eaten and worn, but she relied on her own childhood for details of his travels by land.

Neville also helped Fletcher better understand how humans and animals might communicate without words. Being with Neville gave Fletcher insight into how Arthur and the bear might relate to each other. Arthur hums to calm the bear, and he learns that her chuffs, grunts and withdrawn silence convey her annoyance, excitement and sadness.

How did that happen, Susan Fletcher remembers wondering when she first read a history of the royal menagerie at the Tower of London. The exotic animals in the collection were often gifts from the rulers of other countries to the king of England. But how, exactly, did an Arctic animal wind up there?

“Journey of the Pale Bear” took five years to research and write. Because there were so few facts about the bear, its keeper and their travels, Fletcher imagined the keeper as a 12-year-old boy named Arthur. In the action-packed novel, Arthur and a female polar bear travel from Norway to England in 1252. They brave homesickness, stormy seas and pirates. In one funny scene, Arthur has to clean the poop from the bear’s cage as waves roil the ship.

The bear facts

“They were enormous!” said Fletcher by phone from her home in Bryan, Texas. She compared the 1,500-pound male bear to her dog, Neville, and realized, with a laugh, that “he was the size of 30 Nevilles.”

Growing up in California and Ohio, Fletcher loved to explore the outdoors with her three younger siblings. They would roam for hours through nearby fields and hills and poke around in the pond and creek — just like Arthur and the bear at one point in the book.

Like her character Arthur, Fletcher learned much about polar bears by spending time with them. Thanks to a special invitation from the curator at the Oregon Zoo, Fletcher had a chance to observe two polar bears in a quiet space off limits to the public.

Fletcher knew she wanted to write about that bear, but she also knew she would have to do a lot of research. The bear lived more than 750 years ago, during the medieval period in Europe.

Data from conservation groups and the government show that the polar bear population is roughly five times what it was in the 1950s and three or four times what it was in the 1970s when polar bears became protected under international treaty.

The State of the Polar Report 2018 put the new global mid-point estimate [of the polar bear population] at more than 30,000.

Many of us watched the viral video in horror. A starving polar bear scavenging for food on barren land, his ribs visible beneath a jaundiced white coat.

As Michele Moses recently explained in The New Yorker, scientists accused National Geographic of “being loose with the facts.” There was no evidence, many pointed out, that the bear’s condition was the result of climate change. The bear simply could have been old, ill, or suffering from a degenerative disease.

What Followed

“The story of climate change has been told, in part, through pictures of polar bears,” Moses writes. “And no wonder: in their glittering icy habitat, they reflect the otherworldly beauty that rising temperatures threaten to destroy.”

In fact, though polar bears were placed under the protection of the Endangered Species Act in 2008 over concerns that its Arctic hunting grounds were being reduced by a warming climate, the polar bear population has been stable for the last three decades.

As Moses of The New Yorker points out, polar bears have become an “indisputable image of climate change.”

The video, shot by photographers Paul Nicklen and Cristina Mittermeier on Somerset Island, sparked outcry over the decimation of polar bears due to global warming.

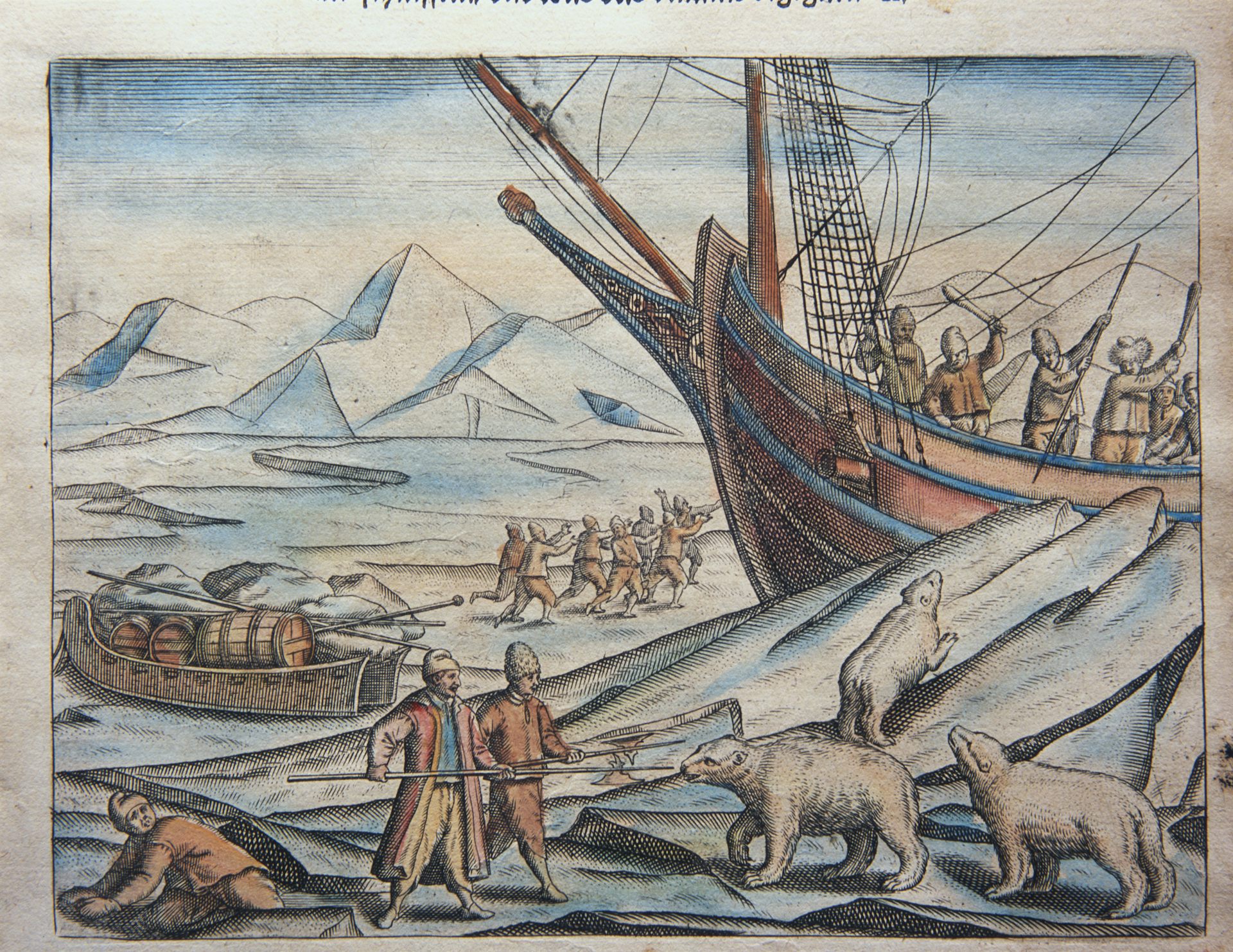

Even Shakespeare may leave a legacy of the fascination polar bears held for Elizabethan audiences. In one scene of “The Winter’s Tale,” a bear chases the character Antigonus from the stage. Historians have suggested that this dramatic exit may have been inspired by one of the live polar bears housed near the Globe Theatre, in London’s Paris Garden.

Co-Director of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Bowdoin College

Despite, or perhaps because of, their association with extinction, the allure of the polar bear seems only to have intensified. One curious reflection of this celebrity comes in the form of endearing anthropomorphic depictions of these wild creatures pitching consumer products like Coca-Cola.

The question has particular resonance as people reflect upon the fragility of our own species in the midst of a global pandemic that has already cost millions of lives.

Disclosure statement

Westerners first encountered polar bears over a millennium ago, when Norse explorers advanced into the Arctic. In contrast to Indigenous representations of the bears, by the 15th century western artists were positioning human beings in opposition to these fearsome hunters as they adorned maps and explorers’ written narratives.

Intriguingly, the artist’s cartoon-like renditions of the “great white bear” seems to echo the illustration included in the press release published by the U.S. Department of the Interior announcing this finding. But Wesley’s drawing raises questions about the fate of the motionless creatures it pictures: is this “celebration” in fact a tragedy?

With the rise of European exploration and exploitation, the cultural legacy of the polar bear spread rapidly among European nations and their colonial outposts. The bears became identified with political and technological prowess, and a triumphant march toward the future. Groups of these giants are called “celebrations,” and their images in art tended to celebrate the brute forces of western modernity.

“I can’t say that this bear was starving because of climate change,” she wrote in National Geographic.

Many of us watched the viral video in horror. A starving polar bear scavenging for food on barren land, his ribs visible beneath a jaundiced white coat.

In 1984, the polar bear population was estimated at 25,000. In 2008, when polar bears were designated a protected species, The New York Times noted that number remained unchanged: “There are more than 25,000 bears in the Arctic, 15,500 of which roam within Canada’s territory.”

Even accepting the lower figure, the estimate is the highest since the polar bear became internationally protected in 1973.

Jon Miltimore

As Michele Moses recently explained in The New Yorker, scientists accused National Geographic of “being loose with the facts.” There was no evidence, many pointed out, that the bear’s condition was the result of climate change. The bear simply could have been old, ill, or suffering from a degenerative disease.

The State of the Polar Report 2018 put the new global mid-point estimate [of the polar bear population] at more than 30,000.

Mittermeier was looking for visual evidence of the future she imagined, one ravaged by climate change. And she found it that day in a starving bear.