If your university has a required format for a dissertation, and particularly if they supply a template, then use it! Start your writing straight into the template, or format your work correctly from the start. There is very little worse than cutting and pasting your work frantically into a template 10 minutes before your submission deadline. Templates are designed to make your life easier, not harder.

If you cannot find any guidelines, then ask your supervisor and/or the person who will be marking your thesis about their preferences. Make sure that the voice and person are consistent throughout.

- How often are they prepared to meet with you during your research?

- How quickly will they respond to emails asking for advice and/or guidance?

- How much time do they need to review drafts of work?

- How many drafts of your work are they prepared to read? University guidelines usually say ‘a first draft’ but many academics are prepared to read a preliminary draft to check that you are on the right track, and then a more polished version.

- Having reviewed a draft, will they send you comments by email, or would they prefer to meet to discuss it?

Academics tend to take a highly personal approach to supervision. Some will be prepared to spend a lot of time with you, talking about what you are planning to do by way of research and your emerging findings. Others will have very little contact with you, apart from being prepared to read a draft of your dissertation.

Proof-reading

However, many journals have now moved away from that convention and request first person and active voice, which would require you to write ‘I carried out an experiment to test…’

You will need to ensure that you build in sufficient time to allow someone else to read over your work. Nobody, not even if you are paying them, is going to want to stay up all night to edit your work because you left it too late. Many will also prefer not to work at weekends. Allow at least two weeks for professional language editing.

The introduction may be the last part you write, or you may wish to rewrite it once you’ve finished to reflect the flow of your arguments as they developed.

A dissertation or thesis is likely to be the longest and most difficult piece of work a student has ever completed. It can, however, also be a very rewarding piece of work since, unlike essays and other assignments, the student is able to pick a topic of special interest and work on their own initiative.

Third, you should point future researchers in directions that will replicate or add to what you have accomplished.

So, let’s take a look at this entire process in terms of the average dissertation project from start to finish.

The question now becomes, how long does it take to write a dissertation proposal? And again, the answer varies. For some students, this is a longer project, because committees, and individual members, can be very picky. They may send the student back to re-write certain parts before final approval. You will discover that every committee member has individual agendas and pet peeves. These will come out in their assessment of your proposal. Do not be discouraged if you have to re-write – it is common and expected.

You will need to explain exactly how you chose samplings or the control and experimental groups (if you have them), and exactly the treatment(s) you used or the information your instruments are gathering from your sample population.

Not Quite Finished – the Introduction and the Abstract

Most students have had experience writing conclusion for essays and papers. But understanding how to write a conclusion for a dissertation will require a different approach. Most dissertation conclusions are highly organized into specific sections.

Just how long to write the analysis chapter in a dissertation? It will depend upon individual students’ abilities to craft it on their own or how quickly they can secure the help they need.

Again, the analysis must be reported in both graphic and prose forms.

Depending upon your institution or department, the data you gathered is either reported in this chapter or the next. Data should always be reported in both prose and graphic forms

It's surprising to see that many students have some level of confidence during the previous two stages of the process, but they crack when they realize they don't really know how to write a dissertation. Remember: you already did a great job up to this point, so you have to proceed. Everything is easier when you have a plan.

The Internet is a good starting place during the research stage. However, you have to realize that not everything you read on the Internet is absolutely true. Double-check the information you find and make sure it comes from a trustworthy resource. Use Google Scholar to locate reliable academic sources. Wikipedia is not a reliable source, but it can take you to some great publication if you check out the list of references on the pages of your interest.

When you get to the point of writing a dissertation, you're clearly near the end of an important stage of your educational journey. The point of this paper is to showcase your skills and capacity to conduct research in your chosen discipline and present the results through an original piece of content that will provide value for the academic and scientific community. You should also make the dissertation interesting and unlike any other academic paper that's already been published.

However, the term dissertation is also used for the final project that PhD candidates present before gaining their doctoral degree. It doesn't matter whether we are talking about an undergraduate or PhD dissertation

Structure of the dissertation proposal

To understand how to write a dissertation introduction you need to know that this chapter should include a background of the problem, and a statement of the issue. Then, you'll clarify the purpose of the study, as well as the research question. Next, you'll need to provide clear definitions of the terms related to the project. You will also expose your assumptions and expectations of the final results.

Now that you've completed the first draft of the paper, you can relax. Don't even think about dissertation editing as soon as you finish writing the last sentence. You need to take some time away from the project, so make sure to leave space of at least few days between the writing and editing stage. When you come back to it, you'll be able to notice most of its flaws.

This is a basic outline that will make it easier for you to write the dissertation:

Now, you're left with the most important stage of the dissertation writing process: composing the actual project, which will be the final product of all your efforts.

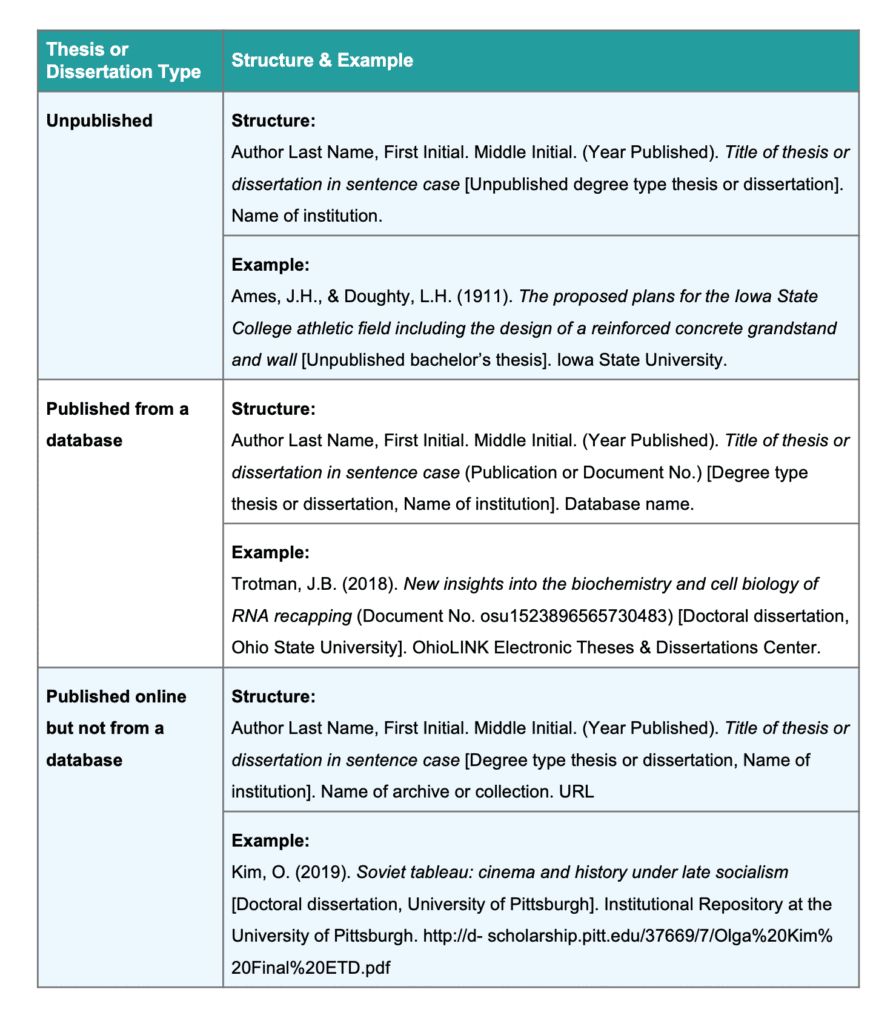

If you are interested in learning more about how to handle works that were accessed via academic research databases, see Section 9.3 of the Publication manual.

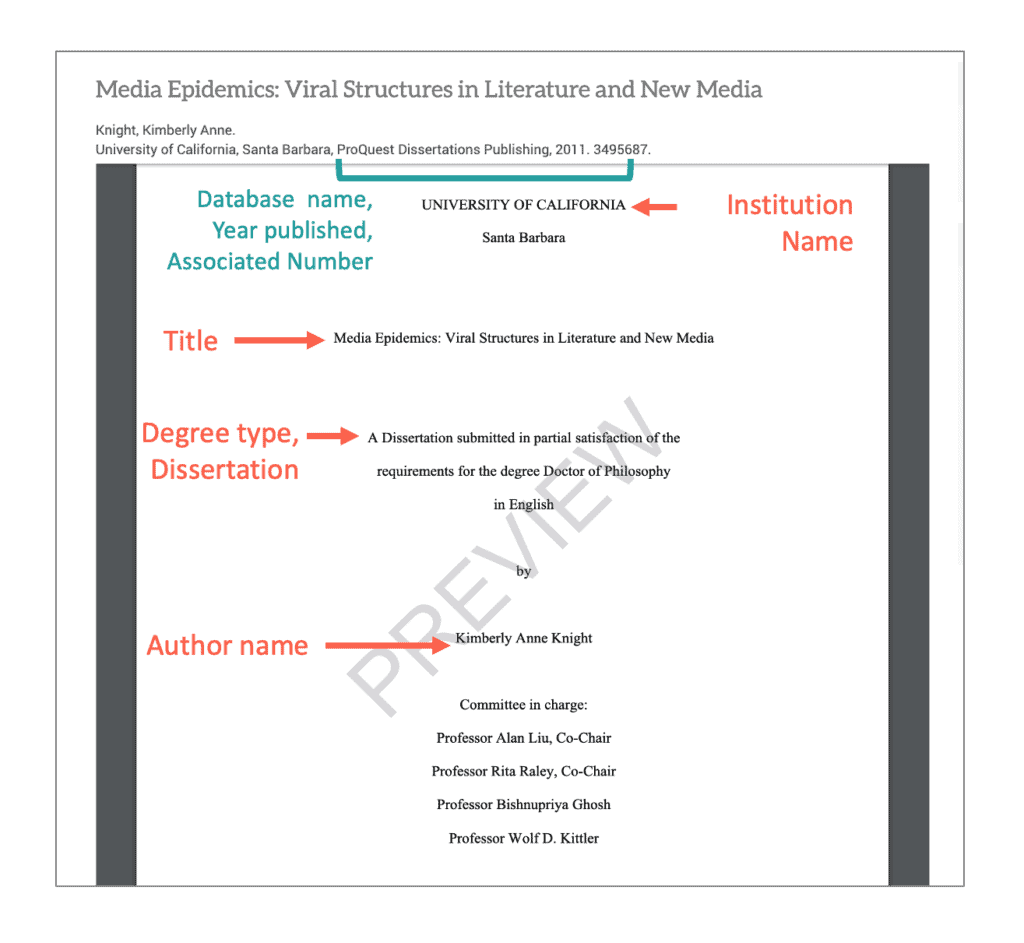

All of the guidelines below come straight from the source: the 7 th edition of the Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (2020a). If you’d like to follow along, you can find the official guidelines on pages 333 and 334. Please note that the association is not officially connected to this guide.

- The institution is presented in brackets after the title

- The archive or database name is included

It is important to note that not every thesis or dissertation published online will be associated with a specific archive or collection. If the work is published on a private website, provide only the URL as the source element.

Citing a Thesis or Dissertation Published Online but Not From a Database

Kim, O. (2019). Soviet tableau: cinema and history under late socialism [Doctoral dissertation, University of Pittsburgh]. Institutional Repository at the University of Pittsburgh. https://d-scholarship.pitt.edu/37669/7/Olga%20Kim%20Final%20ETD.pdf

Trotman, J.B. (2018). New insights into the biochemistry and cell biology of RNA recapping (Document No. osu1523896565730483) [Doctoral dissertation, Ohio State University]. OhioLINK Electronic Theses & Dissertations Center.

- Parenthetical citation: (Kim, 2019)

- Narrative citation: Kim (2019)

American Psychological Association. (2020a). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1037/0000165-000

Here is a second example: Your two secondary data sets may focus on the same outcome variable, such as the degree to which people go to Greece for a summer vacation. However, one data set could have been collected in Britain and the other in Germany. By comparing these two data sets, you can investigate which nation tends to visit Greece more.

TABLE 3 summarises particular methods and purposes of secondary research:

Let’s use another simple example and say that your research project focuses on American versus British people’s attitudes towards racial discrimination. Let’s say that you were able to find a recent study that investigated Americans’ attitudes of these kind, which were assessed with a certain set of measures. However, your search finds no recent studies on Britons’ attitudes. Let’s also say that you live in London and that it would be difficult for you to assess Americans’ attitudes on the topic, but clearly much more straightforward to conduct primary research on British attitudes.

Importantly, you can also re-assess a qualitative data set in your research, rather than using it as a basis for your quantitative research. Let’s say that your research focuses on the kind of language that people who live on boats use when describing their transient lifestyles. The original research did not focus on this research question per se – however, you can reuse the information from interviews to “extract” the types of descriptions of a transient lifestyle that were given by participants.

Types of secondary data

Another external source of secondary data are national and international institutions , including banks, trade unions, universities, health organisations, etc. As with government, such institutions dedicate a lot of effort to conducting up-to-date research, so you simply need to find an organisation that has collected the data on your own topic of interest.

But how do you discover if there is past data that could be useful for your research? You do this through reviewing the literature on your topic of interest. During this process, you will identify other researchers, organisations, agencies, or research centres that have explored your research topic.

Having found your topic of interest and identified a gap in the literature, you need to specify your research question. In our three examples, research questions would be specified in the following manner: (1) “Do women of different nationalities experience different levels of anxiety during different stages of pregnancy?”, (2) “Are there any differences in an interest in Greek tourism between Germans and Britons?”, and (3) “Why do people choose to live on boats?”.

Well, because your unique contribution doesn’t come at the start. It comes at the end!

Bonus tip: If you found a topic that was based on a previous assessment task, see if you can convince the person who taught that subject to be your dissertation supervisor.

Many universities upload their students’ dissertations onto an online repository. This means there are a ton of open, free to access databases of previous students’ dissertations all over the internet.

Look, I know many dissertation supervisors can be disappointingly aloof and disconnected from your research. And relationships can get very frosty with your supervisors indeed.

3. Ensure it’s Interesting to You.

“What are teachers’ opinions of the impact of poverty on learning?”

In other words, you will be able to bypass many hurdles you may face.

Go check that out if you want to write a dissertation on the ‘education’ topic.