- Bad example: Immature, whiny, male-pig Romeo, a male harlot, ruins precious Juliet whom he loved no more than Rosaline.

Essays without thesis statements are easy to grade: simply write an ‘F’ at the top of the paper, laugh, and shuffle up the next paper. Unfortunately, not teaching thesis statements is the sign of a really bad English teacher.

On my way out the door, I noticed all the English teachers were busily grading essays. “Hey, Bob,” I shouted as I stumbled into his classroom, “Not done with those essays yet? I finished mine an hour ago.”

Teaching thesis statements involves teaching what a thesis statement is and then conducting reinforcement activities. Try the following. For an excellent description of thesis statements with examples you could use to teach your class, just click on the link.

Ideas for Teaching Thesis Statements

- W.9-10.1 Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts, using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence.

- W.9-10.1a Introduce precise claim(s), distinguish the claim(s) from alternate or opposing claims, and create an organization that establishes clear relationships among claim(s), counterclaims, reasons, and evidence.

- W.9-10.2a Introduce a topic

I’ve taken these lesson plans and added notes, graphic organizers, and more lesson options to create what I consider an invaluable resource for middle school and high school teachers. It’s only $5.95.

- A quick review of how to write a thesis statement may help.

- Have students create thesis statements on a slice of paper. Collect the paper and read them to the class. Have the class vote on them.

- Do the same activity, but use individualized white boards to record judgments.

- Read thesis statements anonymously. The ones that do not qualify get tossed in the garbage (visualizing what happens to bad thesis statements is powerful). Give students chances to rewrite the thesis statement until they get it right.

- Write random topics on the board and have groups of students brainstorm good thesis statements.

- Require students get thesis statements approved before writing an essay.

“So, none of your students know anything about writing a thesis statement?”

- A quick review of how to write a thesis statement may help.

- Have students create thesis statements on a slice of paper. Collect the paper and read them to the class. Have the class vote on them.

- Do the same activity, but use individualized white boards to record judgments.

- Read thesis statements anonymously. The ones that do not qualify get tossed in the garbage (visualizing what happens to bad thesis statements is powerful). Give students chances to rewrite the thesis statement until they get it right.

- Write random topics on the board and have groups of students brainstorm good thesis statements.

- Require students get thesis statements approved before writing an essay.

Next thing I remember, I was surrounded by angry tax-payers. Angry tax-payer #1 shouted, “Get up you thief! Our tax dollars pay your salary and you’re supposed to teach the children of this great state how to write a thesis statement. I suggest you start teaching thesis statements tomorrow morning, or you’ll pay dearly!” The angry tax-payer clubbed me with a ruler and knocked me out again. When I awoke, I saw lesson ideas on my desk titled “Writing a Thesis Statement.”

- Bad example: Immature, whiny, male-pig Romeo, a male harlot, ruins precious Juliet whom he loved no more than Rosaline.

It includes 10 lesson plans aligned to common core standards, notes, and over 15 assignments with answer keys. All you need to do is print out each assignment, make copies, and pass them out. Here’s a Free Topic Sentence Sample Plan to give you an idea of what the paragraph teaching guide has to offer.

Common Core Standards

On my way out the door, I noticed all the English teachers were busily grading essays. “Hey, Bob,” I shouted as I stumbled into his classroom, “Not done with those essays yet? I finished mine an hour ago.”

3. Have you prejudged the issue by using loaded language? Immature writers manipulate readers through emotionally-charged language.

“You’re a disgrace!” Bob shouted. He moved toward me, stapler in hand.

Essays without thesis statements are easy to grade: simply write an ‘F’ at the top of the paper, laugh, and shuffle up the next paper. Unfortunately, not teaching thesis statements is the sign of a really bad English teacher.

Fifth-grade students often manage to write the story of a weeklong vacation in three sentences when asked to write a narrative. Teach students that writing with meaningful detail can help create a page-long narrative from a five-minute experience. Without reference to writing, take students on a brief walk around the building or outside, asking them to pay attention to feelings, sights, sounds, smells and actions.

Vocabulary is a key element in fifth-grade writing curriculum. Read an engaging narrative aloud to students, such as "My Mama Had a Dancing Heart" by Libba Moore Gray. After the first read, ask students to identify what makes the story an engaging narrative. Focus the discussion on the types of words the author used. Explain that authors paint pictures with words using vocabulary that describes emotions, actions and the senses.

< if (sources.length) < this.parentNode.removeChild(sources[0]); >else < this.onerror = null; this.src = fallback; >>)( [. this.parentNode.querySelectorAll('source')], arguments[0].target.currentSrc.replace(/\/$/, ''), '/public/images/logo-fallback.svg' )" loading="lazy">

< if (sources.length) < this.parentNode.removeChild(sources[0]); >else < this.onerror = null; this.src = fallback; >>)( [. this.parentNode.querySelectorAll('source')], arguments[0].target.currentSrc.replace(/\/$/, ''), '/public/images/logo-fallback.svg' )" loading="lazy">

Moment in Time

< if (sources.length) < this.parentNode.removeChild(sources[0]); >else < this.onerror = null; this.src = fallback; >>)( [. this.parentNode.querySelectorAll('source')], arguments[0].target.currentSrc.replace(/\/$/, ''), '/public/images/logo-fallback.svg' )" loading="lazy">

Take students back in the classroom and ask them to describe everything that they noticed the students doing. Jot these down for students in a loose narrative story example. Compare the details students noticed from zooming in, to the rambling list they first gave you. Explain that in a narrative, it is best to zoom in and give detail on just one or two important elements of the story. Ask students to write their narrative of what they saw when zooming in and share it with partners.

Help students overcome difficulties with what to write about by creating a cache of narrative writing ideas that are ready to use. Explain that meaningful events make the best narratives. Ask students to spend a few minutes discussing meaningful personal stories with a partner. After sharing, have students make one idea list for personal experiences worthy of writing a narrative, which includes a brief description of the idea. Students then create another idea list for stories about other people familiar to them, such as family members, again with a brief description. Instruct students to maintain the list as a resource of narrative writing ideas.

By fifth-grade, students have heard many stories, but when asked to write a narrative, somehow the composition often turns into a long string of rambling simple sentences. Fifth-graders need to develop the tools required to tell their stories. Class writing activities can help students overcome this and learn to write engaging narratives.

Step 2: Chronologically organise ideas and express them using What? How? Why?

Now that students have come up with a ‘why’ for each of their points, they are ready to repeat ‘Stage One’ in order to generate their thesis statement. It’s important to remind students at this point that their thesis statement should appear in their introduction and echo the ideas from the conclusion. This will ensure that there is at least some kind of thread linking both ends of the response together.

When I carried out this activity, I deliberately chose a topic that my class were familiar with to prevent subject knowledge from becoming a barrier to their success. After showing students the plan below (without the red/green writing), I asked them to think about what the overall conclusion could be – making sure to stress that it had to tie together all the ideas from the plan. I then typed out their ideas onto the class model, which they copied onto their individual sheets:

Organising ideas chronologically means there is a logical flow between the paragraphs. There is also an added opportunity to discuss the structural/dramatic significance of the selected moments. I make this quite explicit when modelling planning as it prevents students from viewing their chosen moments as isolated incidents unrelated to the wider text.

Stage One – What’s the Conclusion? Now write the Introduction!

The job of a conclusion is to essentially synthesise the ideas in the main response and put forward an overall viewpoint. Effectively, this is what a thesis does too. The activity below should help students realise this and hopefully increase their confidence in devising a thesis.

For character-based questions, I encourage students to chronologically work through the play in their heads/question explosions and select four key moments/quotes to focus on. They then devise an adjective/phrase to summarise each moment. The adjective/phrase is the ‘what’ and the moment is the ‘how’. Together, they provide a clear focus to each paragraph.

Step 1: Explode the question (don’t forget the invisible ‘and why’)

Once students have become confident with finding the thesis from an existing plan, they are ready to learn how to create a similar plan for themselves. Whilst I avoid prescribing a particular planning strategy, this one is simple, time-efficient and effective in generating a thesis.

Some fifth-graders ramble off in many directions when writing a narrative. Precise writing is a key element in many state standards. Post a large picture of a group of children playing on a playground, or take students outside to observe students there. Ask students what they would write if asked to write a narrative about the scene. Most students describe a list of what each student is doing. Jot down the list of things the students describe. Now, point out two or three playing students. Ask the class to place their hands to their eyes like binoculars and “zoom in" on just those students. Have them watch just the two or three students for a few minutes, focusing on everything they do.

< if (sources.length) < this.parentNode.removeChild(sources[0]); >else < this.onerror = null; this.src = fallback; >>)( [. this.parentNode.querySelectorAll('source')], arguments[0].target.currentSrc.replace(/\/$/, ''), '/public/images/logo-fallback.svg' )" loading="lazy">

Vocabulary is a key element in fifth-grade writing curriculum. Read an engaging narrative aloud to students, such as "My Mama Had a Dancing Heart" by Libba Moore Gray. After the first read, ask students to identify what makes the story an engaging narrative. Focus the discussion on the types of words the author used. Explain that authors paint pictures with words using vocabulary that describes emotions, actions and the senses.

Take students back in the classroom and ask them to describe everything that they noticed the students doing. Jot these down for students in a loose narrative story example. Compare the details students noticed from zooming in, to the rambling list they first gave you. Explain that in a narrative, it is best to zoom in and give detail on just one or two important elements of the story. Ask students to write their narrative of what they saw when zooming in and share it with partners.

Zoom In on Detail

Help students overcome difficulties with what to write about by creating a cache of narrative writing ideas that are ready to use. Explain that meaningful events make the best narratives. Ask students to spend a few minutes discussing meaningful personal stories with a partner. After sharing, have students make one idea list for personal experiences worthy of writing a narrative, which includes a brief description of the idea. Students then create another idea list for stories about other people familiar to them, such as family members, again with a brief description. Instruct students to maintain the list as a resource of narrative writing ideas.

Once back inside, ask students to brainstorm all the words and phrases they can come up with to describe the walk experience as you write them on the board. Ask them to examine the words and phrases, noticing how much information was gained. Have students write the narrative of the walk experience using as many of the words and phrases from the list as they can to describe it. Have students note how the detail and length of their narratives have improved.

Have students create a chart with the headings emotions, actions and senses. Read the story aloud again and have students write down the author’s words that fit each category. Create a class wall chart of the words for student reference. Add to the chart with another narrative at a future date.

Fifth-grade students often manage to write the story of a weeklong vacation in three sentences when asked to write a narrative. Teach students that writing with meaningful detail can help create a page-long narrative from a five-minute experience. Without reference to writing, take students on a brief walk around the building or outside, asking them to pay attention to feelings, sights, sounds, smells and actions.

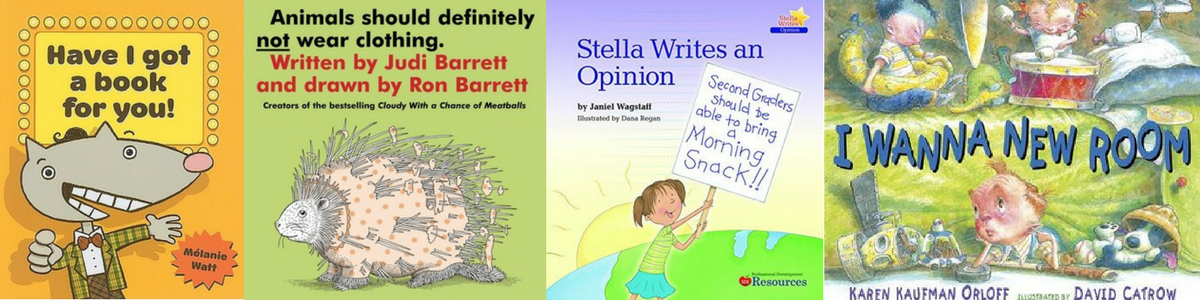

I Wanna New Room by Karen Kaufman Orloff, illustrated by David Catrow

Writing letters to his mom convinced her to let him get his pet iguana, so Alex puts pencil to paper again, this time determined to get his own room.Have I Got a Book for You! by Mélanie Watt

Mr. Al Foxword is one persistent salesman! He will do just about anything to sell you this book. Al tries every trick of the trade.Animals Should Definitely Not Wear Clothing by Judi Barrett, illustrated by Ron Barrett

This well-loved book by Judi and Ron Barrett shows the very youngest why animals’ clothing is perfect . . . just as it is.Red Is Best by Kathy Stinson

Young Kelly’s mom doesn’t understand about red. Sure, the brown mittens are warmer, but the red mitts make better snowballs. No doubt about it, red is best.Books

A Pig Parade Is a Terrible Idea by Michael Ian Black, illustrated by Kevin Hawkes

Could anything possibly be more fun than a pig parade!? You wouldn’t think so. But you’d be wrong. A pig parade is a terrible idea.“Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death!” by Patrick Henry, delivered March 23, 1775,

St. John’s Church, Richmond, VirginiaOne Word from Sophia by Jim Averbeck, illustrated by Yasmeen Ismail

Sophia tries varied techniques to get the giraffe she wants more than anything in this playfully illustrated story about the nuances of negotiation.